USH|R Guest Research Blog, Part II: A Glimpse into a Genetics Lab

December 16, 2015

Laboratory for Molecular Medicine and ClinGen

by Andrea Oza and Danielle Azzariti

Within the Usher syndrome community, we often hear about the importance of genetic testing. For better or for worse, it's one of the only ways to make an early diagnosis, and it is often needed to participate in clinical trials. However, keep in mind that genetic testing isn't required to join the International Usher Syndrome Registry! We wanted to share with you an inside glimpse into the work we do in a genetics laboratory every day, some of the benefits and limitations of genetic testing, and how we are part of a worldwide effort to help people with all genetic conditions, including Usher syndrome. We also want to share how the Registry is valuable to us.

Genetic testing often takes much longer and turns out to be more complicated than some people think. Unfortunately, it doesn't quite work the way that TV shows like CSI would have you believe. Believe us, we wish it was that fast and it always gave a clear-cut, yes or no, answer! One of the biggest challenges, both in the lab and for patients, is the uncertainty that can sometimes arise from genetic test results. We want to go into more detail about how we are trying to reduce this uncertainty. But, before we get into that, let's just go through some background information so we all are on the same page.

Most genetic tests are looking for changes or differences in an individual's genetic makeup that would explain why they have a genetic condition, such as Usher syndrome. Our genetic makeup is made up of DNA, which is composed of an alphabet of 4 letters (A, C, G and T). Our genetic alphabet spells out units of information called genes. The job of a gene is to provide instructions to build a protein. Proteins then perform specific functions in our bodies. It is estimated that humans have over 20,000 different genes! That's a lot of little letters (roughly 3.2 billion, actually!) and instructions for our bodies to carry out. We have two copies of every gene; we inherit one from our biological mom and one from our biological dad. When we do genetic testing, we are looking for changes in the spelling of a gene that would cause it to no longer work, like proofreading a paragraph for a typo. In Usher syndrome, we are looking for a change on both copies of the same gene, and there are nine different genes that cause Usher syndrome. For example, we would need a causative change in both copies of USH2A to determine that the genetic test is positive for type 2A Usher syndrome.

You can learn more about genetic testing here or watch this video "The Animated Genome" from "Genome: Unlocking Life's Code," developed by the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History, NHGRI, and Sanan Media.

New technologies have allowed us to test many more genes than ever before. In the past few years, our laboratory has expanded genetic testing for hereditary hearing loss and related genetic conditions (like Usher syndrome) onto one test that includes over 80 genes. The hearing loss in Usher syndrome is often indistinguishable from other genetic causes of hearing loss, which is why the genes for Usher syndrome are included in this test. For better or for worse, genetic testing is the only way to make an early definitive diagnosis of Usher syndrome before the onset of vision symptoms. We’ve learned that in children with apparently isolated hearing loss, approximately 4% were positive for Usher syndrome on this test. That percentage jumps much higher to about 50% for people who are already suspected to have Usher syndrome and are tested for just the 9 Usher genes.

Ok - so now that we have talked about the basics, let's dive into one of the big issues in genetic testing. If you have already had genetic testing, you may have already heard about the dreaded Variant of Uncertain Significance, or VUS. A VUS is basically a genetic change in limbo between a causative change (ie - it causes Usher syndrome) or a benign change (ie - it doesn't cause Usher syndrome, but is just a difference that is not of medical importance). We all have changes in our genes that make us just slightly different from one another. At the laboratory, we want to be very certain when we make the distinction between causative and benign changes. Imagine getting a diagnosis of Usher syndrome from a genetic test done at 5 months of age, but the lab did not have enough information to correctly interpret the result and actually that person grows up to have completely normal vision. Or imagine having tests at two different labs and Lab A interprets the results as positive, but Lab B interprets the results as inconclusive. What do you do then?

These issues are taken very seriously when we are interpreting genetic testing results. In the past few years, we have been spearheading efforts in the genetics community to improve consistency in how genetic changes are interpreted between laboratories, primarily through defining standards and sharing data. Our laboratory director at the Laboratory for Molecular Medicine, Heidi Rehm, was part of a task group that published guidelines on how to interpret genetic changes. In addition, we have been part of an effort known as the Clinical Genomic Resource, called ClinGen for short.

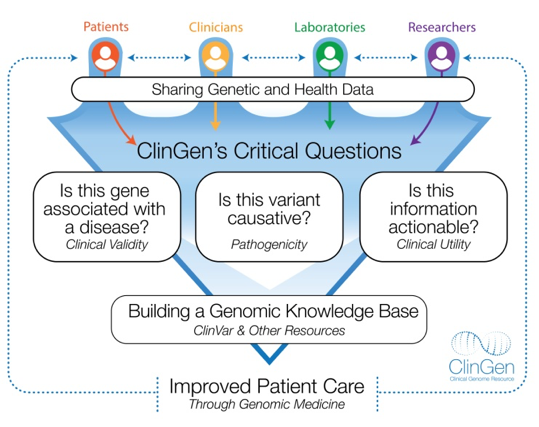

ClinGen is funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and is creating tools and resources to help us understand how genetic changes affect human health by bringing together laboratories and healthcare professionals who are interpreting these changes. ClinGen encourages laboratories to share their interpretations in a public database called ClinVar to collect and compare available knowledge about the genetic changes each lab has seen. ClinGen is assembling groups of experts who focus on specific genetic conditions, including hereditary hearing loss, to evaluate the information that is collected and provide expert interpretations. ClinGen is working on tools to facilitate this process to increase productivity. ClinGen is building an authoritative central resource that defines the clinical relevance of genes and variants for use in precision medicine and research. Information generated by ClinGen is made publically available so laboratories, healthcare providers, researchers and patients can access it.

You can learn more about the ClinGen Resource at https://www.clinicalgenome.org/ or follow them on Twitter @ClinGenResource.

Sharing of information is a central concept of the ClinGen resource, and its clear that sharing of information is an important aspect in precision medicine. Sharing information is also a core concept to the Usher Syndrome Registry, with the same ultimate goal: improving lives, specifically people with Usher syndrome. The Registry will help increase our understanding of Usher syndrome, its natural history, and most importantly, it will help lead to new treatments. The Registry is built from the ground up from the Usher syndrome community FOR the Usher syndrome community. Genetic testing is not required to join! You can learn more about the registry here.

We hope that this post gave you greater insight into the inner workings of a genetic testing laboratory, and also energized you by telling you about the projects we are working on to greater serve both the Usher syndrome community and other communities with genetic conditions. The challenges that we face in Usher syndrome genetic testing are also challenges in other genetic conditions, and we are working on ways to help solve these issues. If you have any questions about the above information, please contact us at amoza@partners.org.

About the Authors:

Andrea Oza, MS, CGC

Andrea is a certified and licensed genetic counselor in Massachusetts. She is currently a genetic counselor at the Laboratory for Molecular Medicine who specializes in hereditary hearing loss and related conditions, including Usher syndrome. In addition, she provides genetic counseling to patients and families in the Department of Otolaryngology at Boston Children’s Hospital.

Danielle Azzariti, MS, CGC

Danielle is a certified and licensed genetic counselor in Massachusetts. She started her career as a clinical genetic counselor and research coordinator for the Massachusetts General Hospital Neurogenetics Program. She has been working at the Laboratory for Molecular Medicine since 2013 as a project coordinator for the Clinical Genome Resource.

Support USH Research | Support the USH Registry

Join the International Usher Syndrome Registry